- Home

- Berit Ellingsen

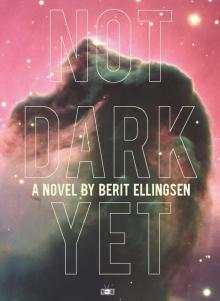

Not Dark Yet

Not Dark Yet Read online

TWO DOLLAR RADIO is a family-run outfit founded in 2005 with the mission to reaffirm the cultural and artistic spirit of the publishing industry.

We aim to do this by presenting bold works of literary merit, each book, individually and collectively, providing a sonic progression that we believe to be too loud to ignore.

COLUMBUS, OHIO

For more information visit us here:

TwoDollarRadio.com

Copyright © 2015 by Berit Ellingsen

All rights reserved

ISBN: 9781937512408

Library of Congress Control Number available upon request.

Cover: The Horsehead Nebula, ESO

Author photograph: Alexander Chesham

No portion of this book may be copied or reproduced, with the exception of quotes used in critical essays and reviews, without the written permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s lively imagination. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

CHAPTERS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

1

SOMETIMES, IN BRANDON MINAMOTO’S DREAMS, he found a globe or a map of the world with a continent he hadn’t seen before. When that happened, a flash of excitement ran through him and he hurried on to explore the new place. Now he had the same feeling of sudden, unexpected discovery, and started running down the fir-shaded hill, stubbed one boot against a stone, stumbled in the soft, rain-sodden ground, nearly fell, and slid the remaining distance to where the grass-covered slope ended in a short overhang of roots and straw. In the pebble-strewn stream that ran beneath the beard of vegetation, he nearly twisted his ankle, making his ninety-liter backpack wobble and the steel canteen bang against his hip, nearly toppling him. But finally, he stood before the blue door on the wooden terrace, his boots caked with mud, his heart beating hard, and the air fragrant with the scent of pine sap and heather and earth. While he caught his breath, he took in the red walls, the unpainted deck, and the gabled roof where the dark eyes of solar cell panels gleamed even in the overcast day.

He felt weightless, only the pressure against the soles of his feet signaled the substance of the rest of his body. The cabin, the heath, the world shone inside him, in an intimate, shared existence. He closed his eyes and there was no body, and no world either, only the simple, singular nothingness he recognized as himself.

When his breath was less ragged and he could focus on something else other than gaining air, he took out his wallet and unzipped the pocket in the back where a small key bulged the brown leather. He pushed the key into the rust-spattered lock and turned it once. It didn’t shift. He tried one more time, putting more weight on the key. The door held an antique ebony handle and had been painted a clear, deep hue without having been sanded down first, leaving craters and fault lines from multiple layers of pigment visible in the surface. A diamond-shaped pane of unevenly sealed glass sat high in the wood, but the window was dark and revealed nothing of the inside. He closed one hand around the handle and rattled the door while using the key with his other hand. The lock didn’t turn this time either, but the door snapped back into its unpainted frame. He gave the door a good push and tried the key again, and this time the lock gave way. He shook his hand from its tight grip on the narrow metal and returned the key to his wallet. Then he pushed with both hands on the handle. The wood creaked open and swung wider to invite him in.

He stooped to avoid the frame and closed the door. Further inside the ceiling grew higher and more accommodating, with more than enough room for him to stand at his full height.

The interior of the cabin was a single space, about five meters in the short dimension and eight on the long. The floor was covered with wide hardwood planks the color of dried blood, edged with fake black nails painted at the ends. He almost laughed when he saw it. The maritime-style ship-deck floors had been popular some years ago, in executive offices, high-end stores, and newly built apartments, but then fallen harshly out of fashion. It had been a long time since he had encountered one. The former owners must have bought the flooring on sale or acquired it from another building, and transported it all the way up to the heath, far away from the ocean and the maritime look alluded to.

All four walls lacked baseboards and the northwest corner missed covering, but a few planks had been left on the floor. If there were tools in the cabin’s lean-to shed the corner would be easy to fix. Otherwise, he’d buy a hammer, saw, and nails the next time he hiked through the heather to the nearest town. The cabin smelled of dust with an undertone of mold. He inspected the walls and ceiling, but found no stains of moisture or blotches of fungi.

The long wall to the east was occupied by the kitchen and consisted of a few cupboards in a delicate eggshell blue, a laundry sink in steel of a type he recognized from his grandparents’ old house on the eastern continent, a small refrigerator at the end of the worktop, and a gas stove with a fat canister of propane gas beneath it. The kitchen was illumined by a rectangular window above the sink, the dim afternoon light bounded by once-white frilly curtains. On the floor was a rug made from rags in primary colors, the old fabric now tangled with dust. The stove was a large four-ring camping cooker mounted on a wooden frame. He hunched by the canister and sniffed. He detected no leakage, but he’d have to check the gauge and tubing in full daylight. The fridge was empty, but clean, a power cord curling to the socket in the wall behind. The cupboards held stacks of plain white plates in two sizes, large and small, and cups and saucers in the same non-patterned design. Some of the glassware was cracked and chipped at the edges. The drawers by the sink contained a red mesh tray of stained cutlery and some dented pots and pans, all gray with dust and the sticky remnants of spider webs. The kitchen ended at the blue-painted door that led to the deck outside.

A tripartite panorama window took up almost the entire west wall, looking out on the moor and the mountain range that constrained it. Dusk had almost swallowed the sky, and dark clouds rushed toward the distant peaks. The draft from the three large windows was palpable, even in the middle of the room. The white frame was gray with dust and the sill beneath it littered with curled-up spider husks and desiccated flies. There were some mouse feces as well, and lumps of brown fur, but he neither saw nor heard any other signs of rodents.

By the north wall stood a sagging three-seat sofa with printed purple poppies the size of human heads, and a long, frilly skirt. Leaning against the south wall was an old lime-green spring mattress. When he touched its surface dust whirled up, yet the smooth fabric seemed dry and free of mildew. He went over to the door, opened it to the dimming evening, and carried the mattress to the deck. The

re he hit the fabric repeatedly to get the worst of the dust off, then stood the mattress on end and bounced it a few times. More particles left to spread on the evening breeze. He sneezed, slapped the mattress some more, then carried it back inside and shut the door against the coming night.

2

BY THE PANORAMA WINDOW WAS A SQUARE PIT IN the floor, filled with lumpy sand. Above it, a bronze hood shaped like the bulb of an onion hung suspended from the ceiling, venting to the roof. A hearth, but with modern ventilation. Although he had seen pictures of the cabin’s interior and exterior, the feature surprised him. In the corner by the pit was a single electrical outlet, which must be connected to the solar panels on the roof.

He creaked across the floor and sat down by the hearth. The sand was dense and caked, not fine and loose as in the traditional houses of his father’s country. He passed his fingertips over the grains like one might water. Something moved in the dark mass and he pulled his hand back. A red centipede, as long as his palm, rushed up from the sand, and vanished into the gap in the northwest corner. He inspected the wool insulation. A tiny crack in the siding brightened to the heather outside, and he hoped the centipede had fled there instead of further inside the wall.

He returned to the hearth and sat there for a good while. When it was almost dark he went outside in the drizzle and pulled a few branches off the tree closest to the deck. It turned out to be a dried-up magnolia, presumably planted by the cabin’s former owner. The twigs carried the remnants of a few flower buds and leaves, long since yellowed and decayed by the fall. The sky above the low peaks on the other side of the heath was black with gathering clouds.

The branches were covered in a fine layer of dried mud and were humid to the touch, but he stacked them in the hearth and held the flame of his camping lighter close to them until they finally caught fire. The light flickered over the night-dark walls and exhaled small breaths of heat which only emphasized the chill in the rest of the room. When the fire had consumed the wood he didn’t go outside to replace it, but undressed to his t-shirt and boxer briefs, pushed the mattress to the hearth, rolled his thin sleeping bag out on it, and fell asleep, even though it was barely six o’clock in the evening.

The next morning he put on running pants and trainers and went out on the deck. The air was sharp and fresh, easily bypassing his single layer of fabric, stealing the heat from his body, but the sensation only made him more alert. Far to the southwest and northwest were the neighboring farms: wooden houses, barns, courtyards, gardens. Except for them the moor held only heather and wild grass. He drank in the bright autumn light, the cold wind, the smell of vegetation and soil, and it felt like something sublimated and left him. He leapt from the unpainted deck and into the flowering heather, the ground firm and dry, not soft and sodden like he had expected, and began to run.

He continued west down the slope of the plain, feeling like he could run all the way to the summits in the distance. It made him think of a story he had read, about a dead man and a blackbird who traveled through a decaying, atrophied world to reduce the heat from the sun. Because the man was dead he needed no rest, and the two crossed a wide moor for days before they ascended into the mountains. Now he wanted to do the same, continue without stop until he reached the round blue peaks that bordered the moor. It looked like it would take at least two days of running. He wasn’t back to that level yet, so it would provide him with a nice goal for the future. He tried to remember which town or county lay on the other side of the peaks, but failed to recall a mental map of the region, his mind unwilling to hold onto anything but the mountains and the heather and the fragrance of the heath.

When the sun glimmered above the peaks, the slanting rays stung his eyes and warmed his skin. The silvery morning light made him feel transparent, clear as glass. He squinted and grinned and ran on in the bright morning until the cabin and its small outhouse were dark spots behind him, and he seemed to be equally distant from it and the peaks. Then he continued back through the vegetation for a long while and arrived at the cabin just as the sun completed its brief autumnal arc in the sky and started falling behind the mountains.

3

HE THOUGHT HIS ARRIVAL ON THE MOOR HAD gone unseen, but the next day people appeared. From the mattress by the hearth he saw shadows moving behind the curtains in the kitchen window. He let the visitors do whatever they wished and pretended not to notice. He wasn’t doing anything that was interesting to watch anyway.

“I see a ghost in there,” a child commented through the door. Someone shushed her and retreated from the deck, their steps shivering the old planks.

“The natives are restless,” he texted Michael.

“Be careful,” Michael wrote back.

“Always,” he replied.

“When are you coming back home?”

“I just got here.”

“What does the cabin look like?”

“Not bad. As in the photos.”

“I miss you,” Michael wrote.

“I’ll be home again soon,” he replied, with no other reassurance than that.

The next day there were even more people, three middle-aged men and a woman, who knocked quietly on his door and introduced themselves as Eric, Pieter, Mark, and Eloise, neighbors. He shook their hands and returned their smiles and let them inside. They filed into the cabin, cluttering the entrance with their shoes, spreading the smell of sweaty feet and the sound of steps on the blood-red hardwood floor. Then they squeezed together on the dusty sofa with pained looks on their faces, while he apologized for the lack of additional seating.

He took out some mugs from the cupboard and asked the guests if they wanted tea. At first they declined, but then they said yes, that would be lovely, so he had to turn on the gas and light the stove and rinse the dusty cups in the sink and heat water in the dimpled kettle and take out some tea bags from his backpack and talk.

“Who are you, where are you from, what are you doing here?” they asked, but in more roundabout terms. He told them that he was from a city south along the coast and that he had recently bought the cabin and its plot. The visitors were from the neighboring farms and after a while he gathered that they wished to lease his land for an agricultural project. They must already have decided that he was no farmer and unlikely to attempt to grow anything on his own.

“You really want to rent the heath?” he nearly blurted out, but stopped himself in time and just said, “Yes, yes, yes.”

They smiled and said, “We’ll come over again soon and tell you more about our plans.”

When they left, he crawled to the panorama window to remain out of sight.

“That wasn’t so difficult,” one of the men said as they sauntered down toward the farms in the southwest.

“Mind your chatter,” came the reply.

He huffed and crept back to the fading fire in the hearth. The moor was only heather and low shrubs. Wasn’t it too cold, the soil too barren to grow anything here?

4

THE CONTINENT’S SPACE ORGANIZATION WAS seeking new recruits for their manned exploration program. It was mentioned in the news only briefly, one story among dozens of others, soon drowned out by subsequent news cycles, but to him it stood out. Those selected as astronauts might be among the first humans to land on Mars. Since most space projects took decades to advance from the first concept to the final launch, the space organization must be well underway in developing the technology and experience needed for the trip.

He sat on the fake ship floor with the laptop plugged into the single outlet from the solar panels on the roof. He had yearned to go to Mars since he was old enough to understand the concept of other worlds. It didn’t matter if the place was inhospitable and remote, had too little air and was too cold and dry. The desire to travel there remained the same. He did wonder if the challenges of cosmic radiation, lack of nutrition, loss of bone and muscle mass, and weakening of the immune system that would happen during the long journey to Mars and back had been so

lved, and searched for information on the space organization’s web pages. He found few answers, but nevertheless returned to the application page and filled out the information the space organization wanted, storing the form online to send later.

Lastly, he took a visual and spatial perception test necessary for the application; he predicted the next geometric shape in a sequence, rotated variously colored blocks in his mind until he could almost reach out and turn them with his hands, and read the numbers off black and white square and round gauges while a timer in the corner rushed the seconds away. When he was done it had grown dark and the log from the wood he had bought in the town center earlier in the day had died out in the hearth. He switched the laptop off, texted Michael goodnight, undressed, and curled up inside the sleeping bag.

“I’ll let you leave on one condition,” Michael had said the last night before he left for the cabin.

He turned on the pillow toward Michael. “I will come back. I promise.”

“It’s not that,” Michael said.

“OK, what is it, then?”

Michael drew a breath. “That you text me ‘Goodnight and I love you’ every night before you go to sleep.”

He looked at Michael. By now he must know he loved him.

He spent the days running and hiking on the moor, forming various routes around the islets of birches, mounds of bilberry, and troughs of cloudberry and cup lichen interspersed in the heather. When he needed more food and firewood, he walked to the town center. In the evenings he watched the news and popular science documentaries on the laptop while it used the power harvested from the sun.

He read about the Hercules-Corona Borealis Great Wall, the largest structure the astronomers had found so far in the universe, a wall of filaments of galaxy clusters ten billion light years across. In its brightly glowing web each tiny point of light was not a star, but an entire galaxy containing billions and billions of stars, many with their own planets, moons, and asteroid fields. He tried to imagine something as large and encompassing as the Hercules-Corona Borealis Great Wall, but it was so impossible, so unimaginable, that he had to go outside on the deck and see for himself the stars that gleamed above the heath.

Not Dark Yet

Not Dark Yet